Non Profit Investment May Be Key To Solving Crisis

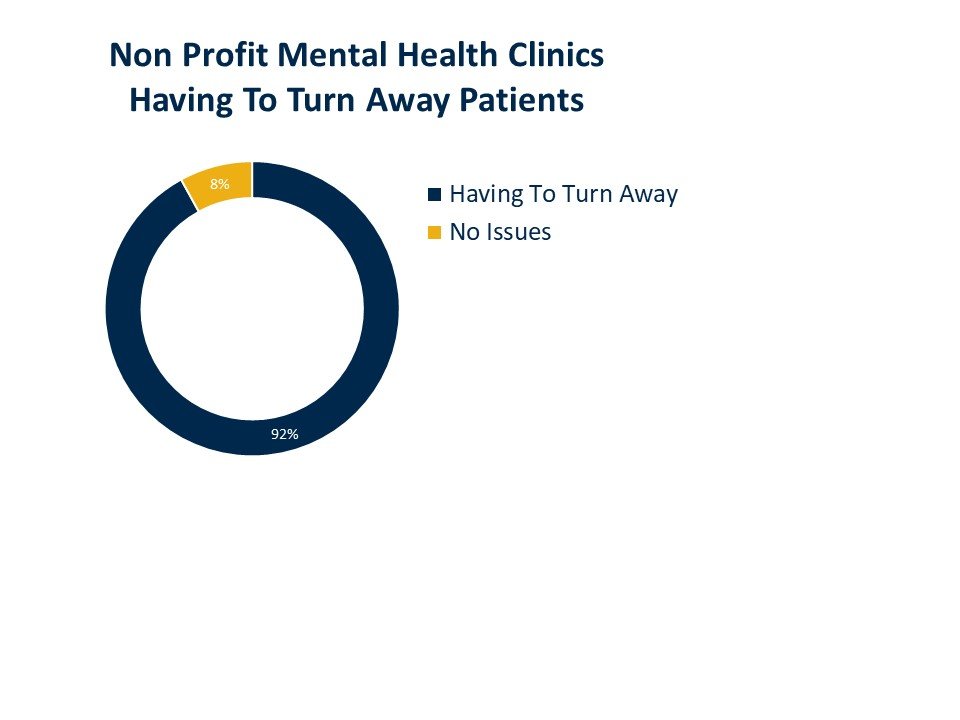

In inner cities like Chicago or New Orleans, it’s difficult to get anyone to show up. On-the-ground counselors just aren’t available. Fred Smith of the Maryville Center in Chicago says many youth they have worked with have been in state custody and either won’t be accepted by hospitals or, if they are, end up getting discharged without a plan after seventy-two hours. Nonprofit community mental health centers and startup mental health centers are often the most vital parts of the ecosystem and will likely be important to meet demand. But many of them struggle to maintain operations given limited funding and difficulty recruiting; 20 of 22 in our poll said they have had to “turn away” patients because they lack the ability to recruit and retain staff like for-profit entities. One nonprofit in California had two part-time psychologists for several years, but both were “scooped up” by a Division 1 collegiate athletic program looking to hire psych professionals for its sports teams.

For supply to increase to meet demand and for outcomes to improve, there is consensus that nonprofits have an important role but need help.

What’s Past Is Prologue

For some context, in 1993 in Erie, Pennsylvania, the nonprofit Safe Harbor Behavioral Health pulled two hundred patients out of a state psychiatric hospital and opened a community mental health clinic. Until then, these patients had been in the hospital for eight to ten years, so psychologist Jonathan Evans took a chance and created a discharge plan for each patient. The patients all had severe mental illness and lives heavily impacted by this illness; with a lot of help, this big idea worked. Only two readmits occurred in the ensuing months, and thanks to advances in pharmacology the community clinic safety net program took off. A crisis response walk-in and hotline service soon followed, along with an eight-bed hospital diversion unit.

It’s not whether investment in non-profit clinics can close gaps in the disparity of mental healthcare….it’s likely more a matter of when and how quickly

“We went from a maintenance-of-therapy model to recovery from illness,” says Evans.

But as with most innovations, growing pains followed. Of the 7,000 patients that made their way through the center over the first few years, 60 percent had a severe mental illness and more than half used street drugs. Their psychotropic medications also created medical issues like weight gain, diabetes, and cardiovascular issues. But this was the mid-1990s, when funding from the Healthy Choice Medicaid MCO and commercial carriers was limited and staffing the center started getting more complicated. The psych staff was moonlighting at night, and others left, leaving more patients complaining about not seeing the same psychiatrist—the same issues many still are complaining about today.

So Evans and his team spun out a for-profit private practice clinic that allowed the clinical staff to stay and earn a living outside the nonprofit. The for-profit “profits” were donated back to the 501c3, and the nonprofit was able to take an administrative fee to develop employee assistance programs. They set up boundaries to allow each to run separately. The clinic was eventually sold to a health system.

Flash forward thirty years to 2023. We are now in the middle of an existential moment for the nonprofit and startup mental health practices. Staffing, scaling, and sustaining great care for complex patients is getting more difficult. Finding labor, getting paid, measuring progress, and dealing with crisis cases is hard work, but the path for nonprofits is potentially improving.

Legal Parameters

Many options have emerged or could emerge in the near future.

One option is to follow what Evans did in forming a separate, transparent, for-profit clinic and work with the community to build it. “This is a way,” emphasizes Tania Malik, JD, but she is quick to note that a second option and greater opportunity likely would be to tap into the supply-demand imbalance and the growing investment dollars available from private equity firms. Malik, former chair of the Telemental Health Special Interest Group for the American Telemedicine Association, says a different option for nonprofits would be to develop an MSO whereby the nonprofit stays that way and maintains total ownership and control of the practice of medicine and all clinical operations, while the MSO “takes on everything but that”: the back office, the payer negotiations, managing revenue cycle, etc. The private equity firm will own the MSO, grow it, and lease back assets from it to the nonprofit, she explained.

A third option is for multiple nonprofits to join and form an independent physician association (IPA). These could involve private equity or leave that out of the mix but give the nonprofits more buying power and more ability to recruit and negotiate better reimbursement with commercial payers. The reimbursement is often a sore spot, given difficulty recruiting and retaining labor these days - an issue Maryville’s Fred Smith attests to.